KENNEDY SPACE CENTER — A liquid hydrogen leak forced NASA to scrub its second attempt to launch the uncrewed Artemis I mission to the moon on Saturday, with NASA saying that the next launch attempt for early next week is off the table.

Even though engine-related issues and a hydrogen leak forced the scrubbing of the first attempt on Monday, there was a separate liquid hydrogen leak that caused officials to call off the launch.

What You Need To Know

- Saturday's Artemis launch attempt has been scrubbed

- RELATED coverage:

The Artemis I’s Space Launch System rocket and the Orion spacecraft are currently sitting at Launch Pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center as it was not sent off at 2:17 p.m. EDT on Saturday for its famed mission to return to the moon.

At around 7:25 a.m. EDT, NASA stated that a liquid hydrogen leak was detected as the fuel was being loaded to the core stage of the rocket. Derrol Nail of NASA's communications department frequently provided updates throughout the day, mentioning various methods engineers used to seal the leak.

NASA engineers went through several different troubleshooting methods to address a liquid hydrogen leak in a cavity in the quick disconnect where the flight side and ground side plates join, the space agency explained.

When no method could be found to seal the leak, engineers suggested a "no go" for the launch. After trying other options, Artemis Launch Director Charlie Blackwell-Thompson finally agreed to scrub Saturday's mission at 11:18 a.m. EDT, said Nail.

Shortly after the announcement of the scrub, NASA administrator Bill Nelson said that scrubs are common and he said it is possible the next launch attempt would be in October.

In fact, during a teleconference on Saturday afternoon, Nelson said scrubs are so common in NASA's history that at one point, the space shuttle went back into the Vehicle Assembly Building multiple times before its first flight. The former astronaut stressed the importance of doing things right.

“We do not launch unless we think it’s right,” he said.

He also started the press conference by saying he was proud of the teams who worked on Saturday's launch.

“While we don’t have the launch we wanted today, I can tell you that these teams know exactly what they are doing and I’m very proud of them,” he said.

Artemis Mission Manager Mike Sarafin said it is unknown what caused the large leak and it started during the fueling process of the liquid hydrogen, from slow fill to fast fill, adding that the teams tried to fix the leak three times but could not.

He also explained that Monday's leak was manageable but the same techniques that were used could not be applied to Saturday's "unmanageable" leak.

Sarafin said engineers will go to the rocket to determine what can be done to resolve the leak at Launch Pad 39B.

While there was some confusion about if the rocket would be rolled back to the Vehicle Assembly Building, Associate Administrator Jim Free clarified that NASA would eventually be returning it to VAB to meet the Eastern Range's requirements and to recharge the Artemis I's system batteries.

"To meet the requirement by the Eastern Range for the certification on the flight termination system, currently set at 25 days, NASA will need to roll the rocket and spacecraft back to the VAB before the next launch attempt to reset the system’s batteries. The flight termination system is required on all rockets to protect public safety," NASA later explained.

Free said the next launch will not happen on Monday, Sept. 5, or Tuesday, Sept. 6. He said the next launch attempt could be Launch Period 26, which is from Sept. 19 through Oct. 4, but admitted that time period might conflict with the scheduled SpaceX Crew-5 launch, which is aiming for liftoff no earlier than Oct. 03.

Launch Period 27 is another consideration, said Free, which is from Oct. 17 through Oct. 31.

During one of the Artemis press briefings during the week, NASA said if Saturday’s Artemis launch were scrubbed, the next attempt would be on Monday, Sept. 5.

But despite the pushback of the Artemis I launch, Nelson said the launches for Artemis II (in 2024) and Artemis III (in 2025) are still on schedule.

Saturday's postponed launch comes days after the first attempt Monday was scrubbed over a separate hydrogen leak.

A scrubbed first attempt

On Monday, Aug. 29, NASA tried to launch the Artemis I mission, but issues came up.

The space agency held three press briefings since it had to scrub Monday’s launch attempt of the Artemis I’s Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and the Orion capsule due to engine issues and a leak. In fact, Monday’s two-hour launch window was set to open at 8:33 a.m. EDT, but those issues forced NASA to place a hold and eventually scrub the mission at 8:35 a.m. EDT.

During Tuesday’s teleconference, Sarafin said the launch would go ahead on Saturday, and he addressed some of the issues that plagued NASA’s engineers.

As the rocket and capsule sat on Launch Pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center, NASA teams were unable to chill down the rocket’s four RS-25 engines to about minus 420 degrees Fahrenheit, with engine 3 displaying higher temperature readings than the others.

The engines need to be thermally conditioned before they can receive the subzero fuel.

The Space Launch System rocket needs 730,000 gallons of super-cooled liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen for liftoff.

Sarafin said a team of engineers addressed that issue, as well as the leak at the tail service mast umbilical on the hydrogen side of the rocket. He added, during a separate Thursday evening briefing, that engineers worked on and successfully repaired the leak.

NASA explained that its teams of engineers replaced a flex hose and a loose pressure sensor line, which the agency believes was the source of the leak, and tightened “bolts surrounding that enclosure to ensure a tight seal when introducing the super-cooled propellants through those lines.”

Sarafin said they have also "worked through a number of issues."

Sarafin also said that there were two risk acceptance: the thermal conditioning of the engines and the cracks in the foam of the thermal protection system on the core stage at the intertank flange.

He said there was a risk that those two items may cause issues, but said NASA was comfortable with its risk acceptance.

"It is a low likelihood occurrence, but something we consider an acceptable risk," he said.

However, those issues did not come up in Saturday's second launch attempt.

But despite the risks, Sarafin said NASA was preparing for a Saturday launch.

"We are setting up for a launch attempt on Sept. 3, Saturday," he said. " … there is no guarantee we are going to get off on Saturday but we are going to try."

Not too shabby of a view on the way out either! #Artemis #SLS #Orion @MyNews13 pic.twitter.com/3MgZeEAImy

— Will Robinson-Smith (@w_robinsonsmith) September 1, 2022

NASA would also be chilling down the engines to about 30 to 45 minutes earlier in the countdown during the liquid hydrogen fast-fill phase of the rocket. This will give NASA more time to cool the engines to the right temperatures for launch and in case the threat of nearby storms will push back the fueling of the rockets, as it did on Monday.

Melody Lovin, a Space Launch Delta 45 weather officer, also said on Friday as she did the night before that there was a 60% chance of favorable weather for Saturday’s launch but stressed that there was a threat of storms near the shoreline. Both a cumulus cloud rule and anvil cloud rule were in place.

She explained the rocket cannot fly into an active thunderstorm and cannot trigger its own lightning — the anvil rule. She said that can happen when rockets fly into a cloud, through a spread of electrical currents in the atmosphere.

However, Lovin said the weather looked “pretty good” for launch time, with the two-hour window opening at 2:17 p.m. EDT.

A second chance

NASA was hoping all would go well for its second shot at lifting off the Artemis I’s Space Launch System rocket and the Orion spacecraft, still currently sitting on the launch pad.

Mission specs:

- Space Launch System rocket: 322 feet tall

- Rocket fuel: 730,000 gallons of super-cooled liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen

- Orion: 10 feet, 11 inches tall and 16.5 feet in diameter

- Mission Duration: 37 days, 23 hours, 53 minutes (it was originally 42 days, 3 hours, 20 minutes before the scrub)

- Total mission distance: About 1.3 million miles

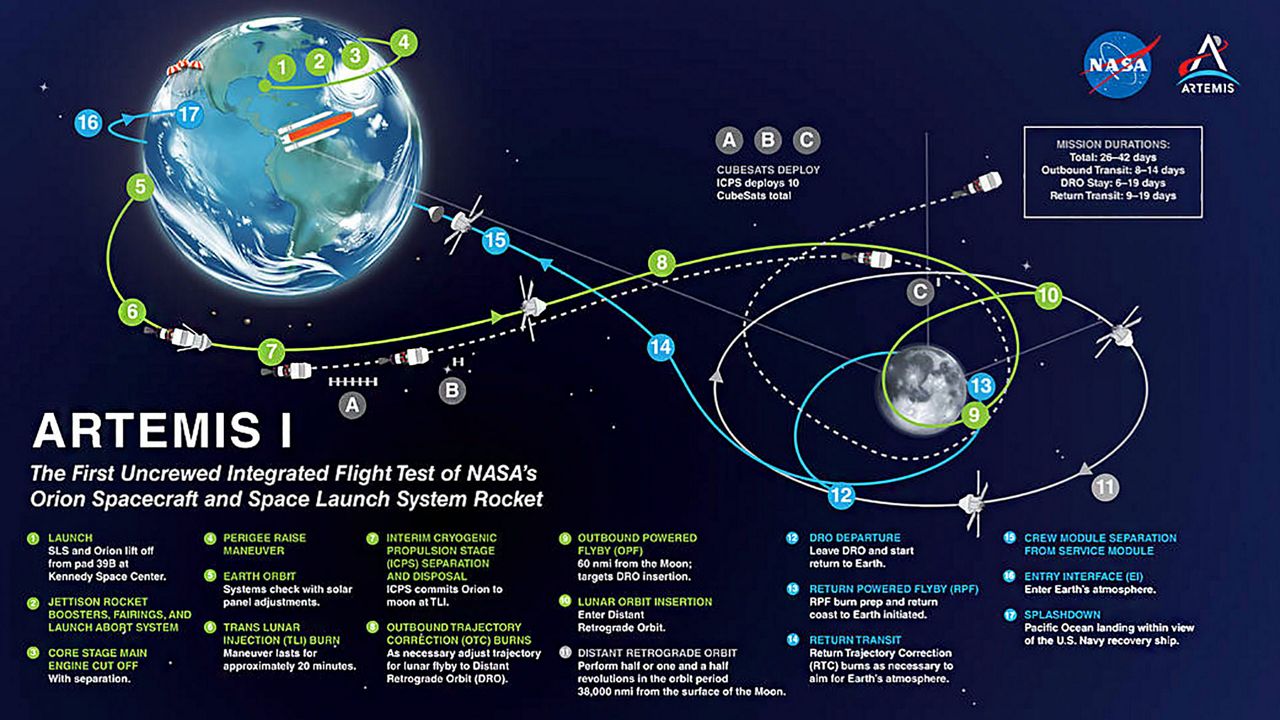

Understanding Artemis I mission

The Artemis program has three missions: Artemis I, Artemis II and Artemis III.

Artemis I is an uncrewed test flight that is designed to provide NASA with information that will be utilized for the two later missions.

Some of the tests that the Artemis I mission will conduct are: getting to the moon, orbiting the Earth’s lunar sister and returning home to test its heat shields and parachutes — because eventually astronauts will be in an Orion capsule and they will want a soft landing.

Once Orion is launched, it will orbit the Earth to gather enough speed to break free from the planet's gravitational pull and head to the moon. But to do that, Orion will use its own rockets (called the interim cryogenic propulsion stage, which is a modified United Launch Alliance’s Delta cryogenic second stage).

As Orion undertakes its days-long journey to the moon, NASA engineers will evaluate the spacecraft’s systems to make sure everything is operating as expected.

While NASA is calling the Artemis I mission uncrewed, in the strictest technical sense, that is not entirely accurate. Cmdr. Moonikin Campos — while not a living person — will be in the commander’s seat, and as an unofficial crew member, will play a big role in the mission.

Decked out in a spacesuit and sensors, the "commander" will record the acceleration and vibrations of the launch and mission, plus take radiation measurements as the spacecraft flies through space.

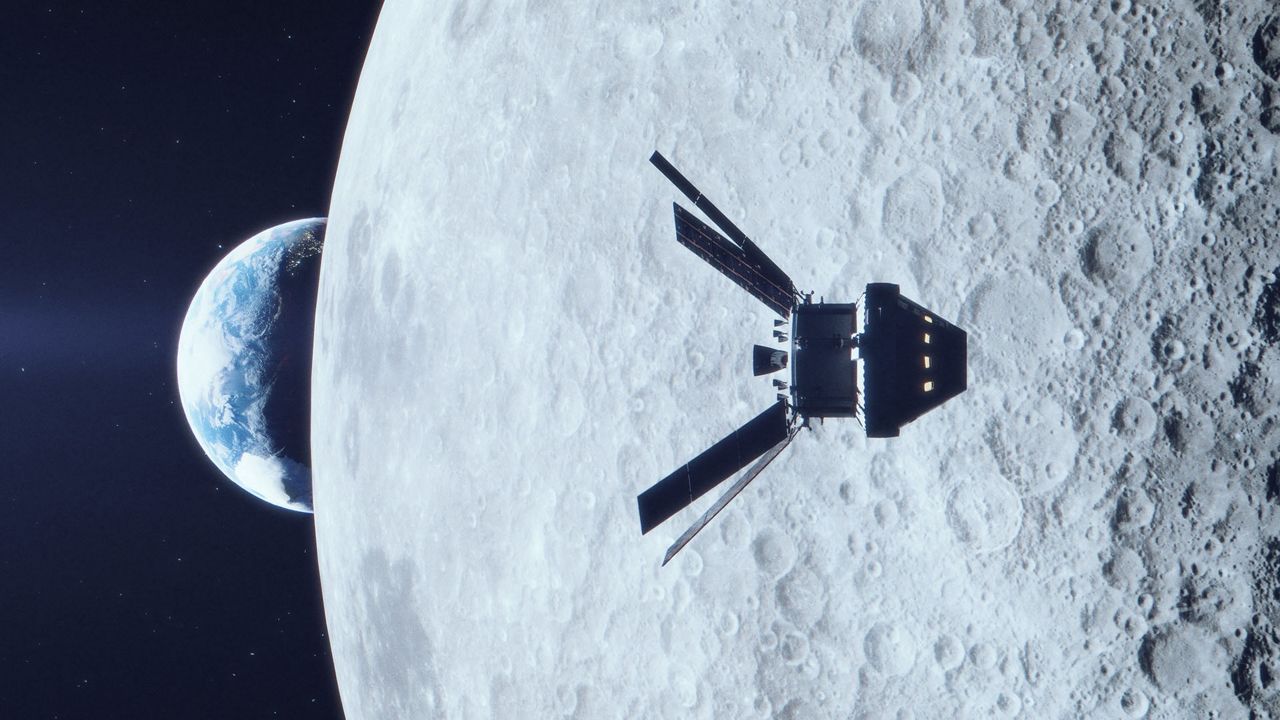

As the brave commander heads to its destination, the engineers on Earth will continue to monitor the Orion craft as it approaches and orbits the moon, stationed about 60 miles above the lunar surface during its closest approach, NASA officials say.

Using the moon’s gravitational force, Orion will be thrust into a distant retrograde orbit, meaning it will go about 40,000 miles past the moon. Experts say, if successful, that will be quite an achievement.

“This distance is 30,000 miles farther than the previous record set during Apollo 13, and the farthest in space any spacecraft built for humans has flown,” information from NASA stated.

When ready to embark on its return trip, the spacecraft, which can hold up to four astronauts, will use the moon’s gravity to slingshot itself back to Earth before firing its rockets.

When Orion does return home, it will be traveling at speeds up to 25,000 mph before the Earth’s atmosphere slows it down to a mere 300 mph.

And therein lies one of the most important tests of the mission: The speed of returning to Earth. As Orion is speeding along at 300 mph, NASA expects it to produce temperatures of about 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit on the craft itself. This will test the craft’s heat shield's performance, NASA stated.

“Our first and our primary objective is to demonstrate Orion’s heat shield at lunar re-entry conditions. So we want to demonstrate that it can withstand the high speed and high heat that the spacecraft will encounter when it re-enters the Earth’s atmosphere,” said Artemis Mission Manager Mike Sarafin during a teleconference back in July.

The splashdown into the Pacific Ocean off the coast of San Diego is expected to happen on Oct. 10.

The other Artemis missions and the future

As scientists and engineers unwrap the findings of the Artemis I mission, they will begin to pave a way for future crewed missions.

In 2024, the plan is for Artemis II astronauts to do a flyby of the moon. Using data from that mission, in 2025, Artemis III will send humans back to the surface of the moon.

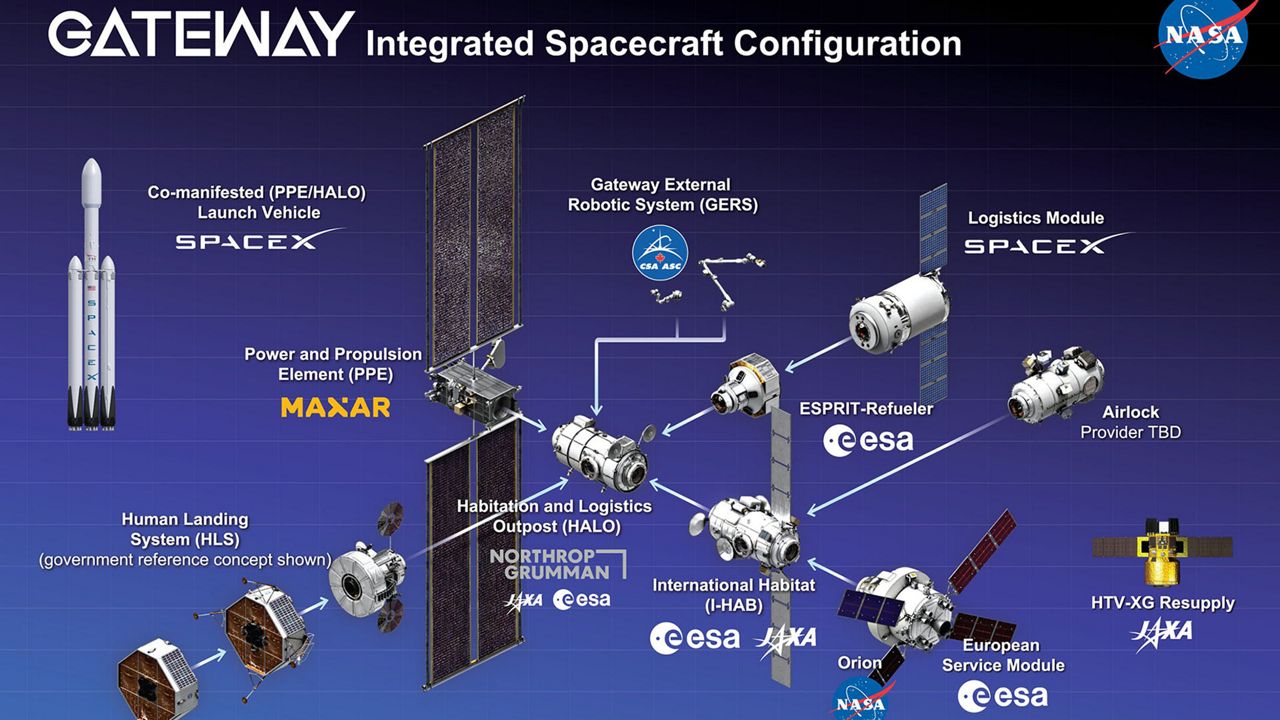

In fact, during Artemis III, it is expected that the world will see the new Gateway space station in action, which should be orbiting the moon by then.

Being built by both international and commercial partnerships, the Gateway will provide exploration and research support and a place for astronauts to live. But it will not just be for lunar visits — space agencies plan to use it to help with missions to Mars in the coming years.