KENNEDY SPACE CENTER — With just over three months until the earliest opportunity for launch, NASA and Boeing, along with other industry partners, provided an up-close look at the progress of the Space Launch System rocket.

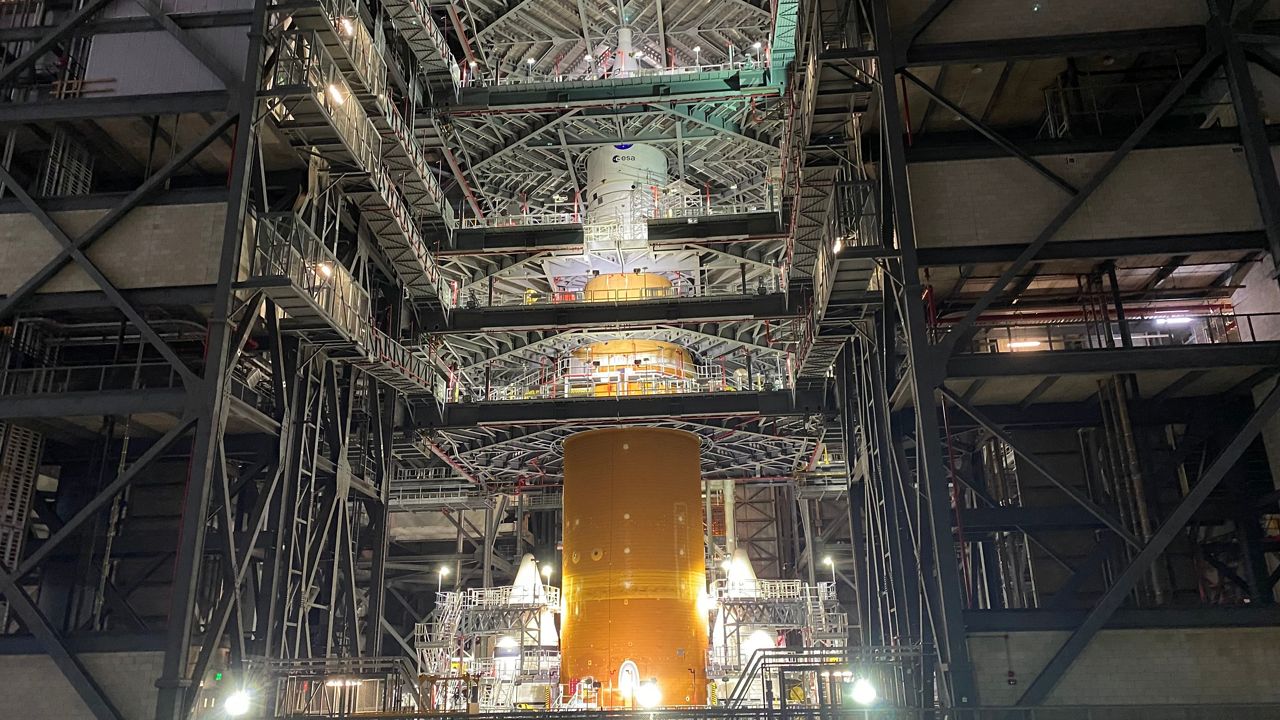

Now fully stacked inside High Bay 3 in NASA’s iconic Vehicle Assembly Building, the 322-foot rocket is going through the endgame preparation before it launches early next year as part of the Artemis program to return humans to the moon.

What You Need To Know

- The Artemis I mission is schedule to launch no earlier than February 12, 2022

- The Space Launch System completed stacking in October

- The rocket will undergo a series of tests leading up to the wet dress rehearsal, which will be the last big evaluation before launch

“This is our first Artemis mission. It’s the first time we’re integrating all this hardware that was designed and built in different, multiple areas,” said Lili Villareal, the operations flow manager for NASA’s Exploration Ground Systems (ESG). “The wonderful thing about our program is we are the ones who get all the components, we integrated together and we integrate all those people that worked for many years with the design and seeing it come to light.”

According to NASA, the unmanned Artemis I mission will travel to the moon, where it will fly in orbit for six days before returning to Earth. The entire mission will last about three weeks and will travel more than 1.3 million miles.

"During this flight, the spacecraft will launch on the most powerful rocket in the world and fly farther than any spacecraft built for humans has ever flown," NASA said on its Artemis I website.

SLS was announced back in September 2011 as the next crew and cargo vehicle in the shadow of the space shuttle’s retirement.

“President Obama challenged us to be bold and dream big, and that's exactly what we are doing at NASA. While I was proud to fly on the space shuttle, tomorrow's explorers will now dream of one day walking on Mars,” said former NASA Administrator Charles Bolden at the time.

The goal of SLS to return humans to the moon to stay was announced in 2017 and named the Artemis program in 2019 under the Trump administration.

Fast forward to today and the Artemis program is getting closer to its final assessments before it’s ready to launch.

“There were so many check marks before, but there are just a few more check marks to go through,” Villareal said. “It’s really amazing how we’re almost there, you know? It’s so exciting.”

Before the ESG team brings the rocket to Launch Complex 39B for a wet dress rehearsal in early January, Villareal said they are aiming to conduct an end-to-end communications check in December.

“Now that we have the vehicle integrated, there’s a series of integrated verification tests that we’ll go do leading up to the big comm end-to-end test,” Villareal said. “And that’s the test that we really want to hit because of the timeline that we want to do it by. And after that, we’ll do a couple more significant tests in preparation for wet dress.”

After the wet dress rehearsal, which involves loading propellant into the vehicle and going through a simulated countdown, the vehicle will be rolled back to the VAB. At that point, they will close out the vehicle and install some payloads flying aboard and prepare for the roll back to the pad for the launch itself.

Pandemic struggles

The last couple of years getting to this point have not been without their challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic caused a number of work restrictions.

“Yeah, there were a lot of obstacles that I think the team has gotten through to get to this point with that pandemic, like you mentioned, and all the storms that we’ve had at our production facilities,” said Elkin Norena, NASA’s manager of the SLS Resident Management Office. “Getting the team to work remotely and then together, it’s been a lot, but we’ve gotten here together and it’s been an interesting journey.

In March, the NASA Office of Inspector General released a report dubbed the “COVID-19 Impacts on NASA’s Major Programs and Projects.” EGS officials said NASA had “an estimated $12.1 million cost impact due to COVID-19 for FY 2020.”

For ESG, the report estimated an additional $53.4 million impact for FY 2021 and beyond “stemming from anticipated schedule slips, such as those related to Mobile Launcher 2 as a result of COVID-19 inefficiencies, and dependencies on flight hardware deliveries.”

Some parts of the Artemis program were more fortunate. Amanda Stevenson, the Artemis II Crew Module Adaptor (CMA) assembly operations lead for NASA, said they didn’t face too much setback on time from the pandemic.

“We actually haven’t seen much of an impact at all to our schedule from the pandemic. Those of us that could work at home, did work at home,” Stevenson said. “No meetings were stopped. There was no shortage of WebEx meetings. We still kept things going.”

The Orion program didn’t escape financial impacts from the pandemic though. The Inspector General report noted that “as of October 2020, Orion and Artemis officials reported an estimated COVID-19 impact of $5 million in FY 2020 and $66 million for FY 2021, including $7 million for Artemis I, $12 million for Artemis II and $47 million for cost and schedule impacts related to the supply chain.”

It also noted that one of Lockheed’s suppliers was impacted by the shutdown of Michoud Assembly Facility (MAF) in Louisiana. In March 2020, then NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine announced that the space agency would temporarily suspend production and testing of the SLS and Orion hardware at the MAF and Stennis Space Center (SSC) in Mississippi due to the pandemic.

Work didn’t resume until mid-May when the MAF moved from Stage 4 COVID-19 response down to Stage 3.

Launching to the Moon, inspiring on Earth

The Space Launch System stands at a towering 322 feet in height, taller than the Statue of Liberty.

Boeing is the prime contractor on the rocket, but the SLS program is an undertaking of more than 1,000 companies from across the U.S. and overseas. The program is managed by NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in Huntsville, Ala., and works closely with the Orion Program, managed at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) and Exploration Ground Systems at Kennedy Space Center (KSC).

The undertaking has provided countless opportunities for people like Brandon Burroughs. After graduating college, he was a SLS Loads and Dynamics Analysts intern with Boeing for almost two years in Huntsville before becoming a systems engineer at KSC for the past nearly five years.

He said ambitious programs like SLS can be good ways to inspire those in grade school to pursue careers in the STEM fields.

“It’s great to have come from that, being that kid that was inspired by programs, like the shuttle program and now being seat where I’m working on the SLS,” Burroughs said. “I just basically think to myself, ‘Don’t forget the important things that you wanted to hear when you were at that age or that point in your education.’”

Orion prepares for people

Atop the SLS rocket is the Orion spacecraft, for which Lockheed Martin is the prime contractor. For the first launch as part of the Artemis I mission, there won’t be any crew on board the module and it won’t include all of its components.

Amy Marasia, the spacecraft assembly branch manager for NASA’s Orion Production Operations said that while the first Orion capsule is ready to go, they are about two-thirds of the way through completing the second capsule, which will fly on Artemis II.

She said the NASA and Lockheed teams learned a good deal from their first go around.

“Definitely some process improvements between Artemis I and Artemis II using new innovations and technology,” Marasia said. “So, using virtual reality to locate parts and install them on Artemis II, 3D-printed stand-in parts so that we could get alignment issues or things worked out early before we installed the actual components. And then just the general flow of the work.”

The Orion spacecraft for Artemis II will also include more crew components than its predecessor. For instance, the second capsule will have all four crew seats, while the first only had one. Waste management systems will also debut with the second capsule as well as the second large, console display and all the life-support systems.

But it’s not just those two Orion spacecrafts that NASA and Lockheed are working on. The pressure vessel for the Artemis III Orion capsule recently arrived from the MAF.

“It’s the bare shell, but it’s the beginning of its journey to becoming a spacecraft,” Marasia said. “So, for the Artemis program, I think the excitement is overwhelming. We are obviously very proud of the point that we’re in, the work that’s being done by both our prime contractor and all of our NASA partners. Suppliers are across the country.”

As part of the Orion program, the second capsule will soon be mated with the European Space Agency’s European Service Module (ESM), built by Airbus Defense and Space, and Lockheed’s Crew Module Adapter (CMA).

“Having ESA and Airbus here is just very insightful in terms of combining not only knowledge, but combining cultures as well of how to do things in engineering,” Stevenson said.

The ESM is described by NASA as “the powerhouse of the spacecraft.” It offers in-space maneuvering, life support (like oxygen, nitrogen and water), temperature control and power. Out of its 33 engines, the main engine is a refurbished Orbital Maneuvering System-Engine (OMS-E) from a Space Shuttle Orbiter.

“It’s actually been really helpful for us, especially with the OMS-E engine or the Orbital Maneuvering System, which we have a lot of history on,” said Michael Dynakowski, an early career systems engineer. “Some of these engines have flown on several shuttle missions, so we know how they’ll perform, so we know what we’re going to expect when we launch these Artemis missions.”

The first ESM is already integrated on the SLS and the second arrived at KSC from Germany on October 14.

That was the same day that United Launch Alliance (ULA) was rolling its Atlas V rocket to the pad at Space Launch Complex-41 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station ahead of the launch of NASA’s Lucy mission to the Trojan asteroids.

What comes next?

As NASA and its partners press on towards the “no earlier than” launch date of February 12, 2022, they will work on the final checkouts of the SLS and conduct the wet dress rehearsal in early January, if all goes well.

At the same time, progress continues with Artemis II. While the second Orion crew capsule continues its progress, ULA has its big contribution, the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage (ICPS).

The 45-foot tall piece of hardware is a modified version of the Delta Cryogenic Second Stage used on ULA’s Delta IV Heavy rocket. ULA manufactures the ICPS in Decatur, Alabama, near Huntsville in partnership with Boeing. It provides 24,750 lbs. of thrust, which helps accelerate the Orion spacecraft to more 24,500 mph “to escape Earth orbit.”

The first three Artemis missions will be supported by the ULA-built stage. The ICPS for Artemis II is currently housed at ULA’s Horizontal Integration Facility at the Cape. It will later be brought to the Delta Operations Center and await integration with the second SLS.

The Artemis II mission will be the first of the program with astronauts on board, but the specific people flying have not been announced. NASA announced 18 astronauts who form the Artemis Team. Two of them, Raja Chari and Kayla Barron, are preparing to launch to the International Space Station as part of the SpaceX Crew-3 mission.

While the astronauts have yet to be named, a 2020 agreement between NASA and the Canadian Space Agency determined that one of the four Artemis II crew members will be a CSA astronaut.