ORLANDO, Fla. — Did you know the federal Home Mortgage Disclosure Act requires lenders to report data on you, when you apply for a home loan? That includes not only what your financial situation looks like, but also your race, ethnicity and gender.

What You Need To Know

- Spectrum News 13's exclusive analysis of home loan data reveals racial disparities

- Blacks and other minorities are denied loans at higher rates than white applicants

- Facing the hard facts: As families struggle to achieve homeownership, data prove the disparities

- Searching for real solutions: Home loan inequality remains, but some people are making progress

- Understanding the methodology behind the data

The Spectrum News 13 Watchdog team dug into that data for the Central Florida area and found lenders deny people of color at a significantly higher rate than white applicants.

Spectrum's exclusive analysis found that over the past three years, on average, 53% of Black applicants in Osceola, Orange, Seminole and Lake counties were approved for home loans. By comparison, 56% of Asian and Hispanic/Latino buyers and 64% of white applicants received loans.

The gap between white and Black buyers stands at 11%.

But barriers to homeownership in America are nuanced. While credit scores and debt are often cited as the main determining qualification factors for home loans, what previous generations of families passed down — or did not pass down — also plays a role. For many families, that lack of generational wealth is a result of red-lining that happened in the early to mid-1900s.

That was the practice of literally drawing red lines on maps around minority neighborhoods and actively denying people within those lines the opportunity to achieve homeownership and build wealth.

But in 1968, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act, outlawing housing discrimination. That changed the rules — but the current secretary of Housing and Urban Development, Marcia Fudge, says it ultimately failed to level the playing field.

In Orlando, aptly-named Division Avenue serves as a modern reminder of that history of inequality.

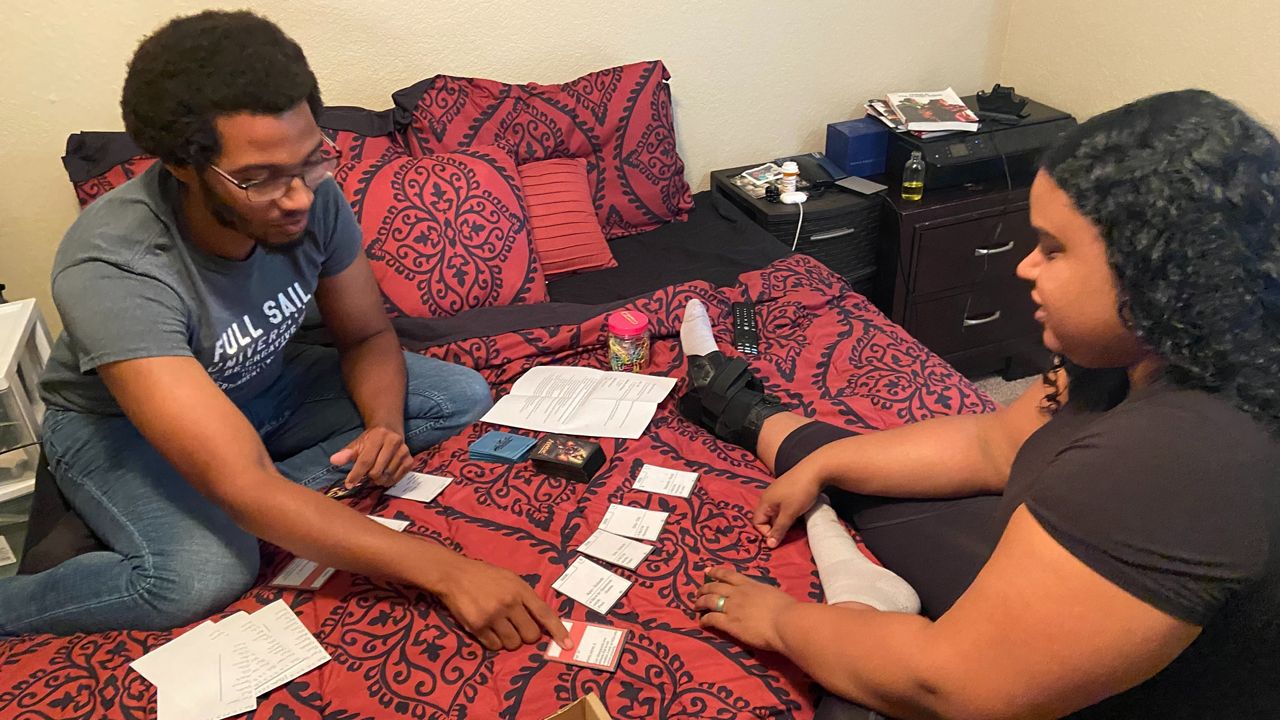

Trevonne and Franchesca live in Central Florida and say they're living proof of the ongoing struggle for some people of color to realize their "American Dream" of homeownership. They recently celebrated their one-year wedding anniversary and had hoped to buy a home. But without a loan, they're still living with Franchesca’s mother in a two-bedroom apartment.

“I was actually really, really upset," Trevonne said, talking about the second time he was denied a home loan back in July. "I checked everywhere. I checked my credit, and they were pulling up a 600 credit score. I was pulling up Credit Karma. I couldn’t find anywhere I was sitting at 600 or anything they were talking about a missed payment.”

Trevonne says, with his credit in the mid-600s, he thought he would qualify.

Spectrum News 13’s data analysis revealed from 2018 to 2020, 49% of all loan approvals were for white applicants, 8% were for Black applicants, 22% for Hispanic or Latino applicants and 5% for Asian applicants.

Now, compare that to the demographics of Central Florida. In the areas around Orange, Osceola, Seminole and Lake counties, 18% of the population is Black, and nearly 32% is Hispanic or Latino.

Trevonne, who is Black, says he’s had to learn on his own how to manage money — and the learning curve has been steep. His mother had multiple sclerosis and couldn’t work, so she, Trevonne and his brother lived on Social Security and food stamps.

“It’s emotional for me," Trevonne said. "When she was smoking and had MS, she’d be really weak, so she wouldn’t be able to do a lot of stuff. So, she taught my brother and I how to cook so we would be able to cook for ourselves and for her."

He says with the help of Habitat For Humanity, his mother became a homeowner, but ongoing financial issues forced the family to move out. Trevonne said those life experiences shaped his understanding of finances and homeownership.

Now, both he and Franchesca are eager to begin a new chapter, just the two of them. She and her mother are incredibly close, but being roommates, “it’s typically not how you want to start out married life,” Franchesca said.

Trevonne is working to improve his finances, both credit and savings, and hopes to apply for a home loan again sometime next year.

But even just applying for a loan isn’t in the cards for many, including Tavish Williams, who is working two full-time jobs while pursuing his true passion for music. He’s hoping to create his own music label to produce and manage artists.

“My dreams come true based off of other people’s dreams coming true,” he said.

To pay the bills, Williams does remote security during the day and sanitation work at night. In between, he’s earning his masters’ in business management and hopes to own a home one day.

“I feel like there’s a few strikes against me before I even apply,” he said.

Williams currently rents a 750-square-foot apartment for $800 a month. He says he didn't learn much about credit growing up, but now he's working to get his scores up. Several years ago, when he went to apply for a loan, he felt pushed out the door.

“It was kind of like — it was more so a turn away than actually taking my information and seeing if I’m qualified,” he said.

Experts say he's not alone.

According to the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, many Black Americans are “soft-denied” by agents — discouraged from even submitting a home loan application.

Shy Bryant shares a similar story.

“Where do I start? I’m the story you don’t really hear about,” she said, talking about the emotional and financial struggles she faced growing up in South Florida's foster care system.

After aging out, she was placed into a mental health facility, experienced homelessness and also went to prison.

But Bryant got her life together, at least for a while. Before losing her construction job last year, her family was financially stable and they were looking to buy a home — a process she called a “battle," saying real estate agents didn’t want to work with her.

Bryant believes her race played a role.

“My image shouldn’t define whether you want to work with me as a Realtor or not. My image shouldn’t define whether I should be accepted in this HOA community,” she said. “I tell them — just try to be Black for one day. One day. One day to understand because people will never understand.”

According to the latest census data, Bryant 's neighborhood is only 25% white but has a home loan denial rate of 18% for white applicants versus 42% for black applicants, according to Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data.

“Some days, Black people wish they were white," Bryant said. "They won’t say it. I would sometimes, not just because of the skin color but because of the opportunity."

She now spends at least 9 hours a day delivering food — a job that is barely making ends meet. But Bryant keeps a positive attitude through it all, saying she has no other option but to be the fighter she is.

And despite the setbacks she has experienced, Bryant remains determined to own her own home.

“Most people want to be homeowners by the time they’re 30," she said. "We’re all in the same race, just in different lanes — you may get there before me.

"I may not be a homeowner before 50, but if I can be a homeowner before I die, that’s my goal."

Nationally right now, Census data reveals just 45% of Black households own their homes, compared with 74% of white households. That means the racial homeownership gap is still no better than it was back in 1968, when fair housing laws were passed in the U.S.